Before you start reading, please be aware of a few things. First, this blog post is meant as a description of an experience that got me out of my comfort zone and addressed some of the racial tensions in my city. It isn't meant to blame or rile anyone up. Remember the purpose of my blog? It's a place to record the happenings of my little family, and a place where I can process through writing. This blog is not a political arena. Secondly, the people who experienced this with me were encouraged to be honest, non-judgmental, and approachable. When you go into a situation with those expectations, it makes you more vulnerable and willing to forgive things that are said that might not normally be spoken aloud. Lastly, this is a really long blog post. For the sake of brevity and because the people I experienced this event with became comfortable with these terms, I refer to African Americans as black and Caucasians as white. I do not use those words intending to degrade or offend, so please forgive me if I have done so. Now, on with the story!

Two weekends ago, I had an experience that changed my thinking on racial reconciliation in our country, in general, and in St. Louis, specifically.

It's called a Sankofa, a word I had never heard before January of this year. I didn't fully understand it until I experienced it, and I'll try to give you the best insight I can. But there comes a point when words can't express what an experience involves, so I highly recommend you tackle something like this yourself.

In January my friend Gina invited me and our other best friend, Kristen, to attend an event called a Sankofa, hosted by her sister Jenny's church. Gina described it like this:

What exactly is a Sankofa? Here's one explanation I found online: "Sankofa is a sacred ancestral term from the Akan people of Ghana, West Africa and can be translated as 'We must go back and reclaim our past so we can move forward - so we understand WHY and HOW we came to be who we are today!'"

What exactly is a Sankofa? Here's one explanation I found online: "Sankofa is a sacred ancestral term from the Akan people of Ghana, West Africa and can be translated as 'We must go back and reclaim our past so we can move forward - so we understand WHY and HOW we came to be who we are today!'"

The Sankofa symbol is a mythical bird with feet facing forward while the head rotates backward. This image illustrates the idea of forward direction while acknowledging where you've been.

I didn't fully grasp what these explanations and concepts mean, but accepted Gina's invitation to join her and Jenny.

Why would I say yes to something I didn't quite understand? Something that sounds likely to be awkward and intense? And something that sounds, to a person like me (who has been known to insert my foot in my mouth on numerous occasions), like a situation where I'm likely to say words or act in a way that is very ignorant and will result in more foot-mouth experiences?

I said yes because Gina, Kristen, and I have been talking about bridge building for a few years. There's a quote by JF Newton that says, "We build too many walls and not enough bridges." My friends and I have taken that to heart, talking about how to intentionally seek people who are different than us so we can cross the barriers and dividing lines that seem to separate us. We've been challenging and encouraging each other to do this with people of different gender identities, faith backgrounds, sexual preferences, and skin colors.

The Sankofa seemed to align with those intentions, so I said yes! (Unfortunately, Kristen couldn't make it - but I'm pretty sure she'll be on the next one!)

I wasn't quite sure what to expect, but I showed up with an open heart and a praying soul. God walked with me throughout the day (and into the next 24 hours, too - a story for another post), and I'm so excited and humbled to share my experience with you here.

Before I get to the exhaustive details of the highlights and stops we made, let me give you the bird's-eye-view of what I carried with me when it was over.

My first emotion was humility, due to my ignorance. I admit I was uneducated (and still am!) about a number of system-wide policies that were placed on blacks in our country. I knew segregation existed in the past, but I considered it ancient history. And if not quite ancient, at least it was long enough before I was born that it feels ancient. Thanks to the Sankofa, I realized these things aren't ancient, nor are they exactly history. They're current events. And the fact that I was so ignorant of these things makes me cringe, because I'm embarrassed to admit my vantage point never covered other people's views.

My amateur education in race relations started with some videos I watched before the Sankofa and a few articles I read, like these:

Since I didn't grow up in St. Louis, I was unaware of the history of race relations in my city. The outbursts and emotions that surfaced after Michael Brown's shooting in Ferguson caught me by surprise, but I've heard from other native St. Louisans that it wasn't a huge surprise for them. Watching those videos I linked (above) and reading that article educated and awakened me to new views.

But it wasn't until I experienced the Sankofa that my education transformed from information into narration. The information went from my head to my heart.

We started the morning meeting at a church in St. Ann. We made introductions and got an overview of the day, and Stephanie (our leader) asked us to be brave and mingle with other people we don't know. She even went so far as to ask the white participants to make an effort to sit by a black participant on the bus so we could share our stories. After praying, we boarded a school bus and our trip began.

I sat with my friend Mary, who I already knew because we used to work together at our church. We also went to Guatemala together last October, so it was like a bus reunion of sorts for us. Mary started chatting with others across the aisle, and the black woman in the seat in front of me turned around to introduce herself. Her name was Tasha, and she asked me if this was my first Sankofa.

Poor Tasha, she asked me one question and my awkwardness took over. I was so afraid of saying something stupid or offensive that I just started a verbal vomit of the story of my friend inviting me and Kristen on the trip. I told her how the Bridge Building mindset started for me, when my gay friends asked me to speak at their wedding. That gave us common ground, as she asked me about how I've talked with my kids about homosexuality. She said she's been wondering how to start the conversation with her five- and six-year-olds, and I was happy to share my experience. (Poor Tasha, listening to me ramble!)

We arrived at our first stop of the day: Canfield Drive in Ferguson, where Michael Brown was shot by a police officer in 2014.

Before the Sankofa started, I knew we'd be going to this place and it was the stop I was most nervous about. Like the rest of the country, I had seen television footage of the scene at Canfield Green Apartments plus hours of video of protests and riots in Ferguson. I had assumed Ferguson was a dangerous place, and Canfield Green Apartments would NOT be a good place for a white person to be. I don't know what I imagined would happen: would black residents be annoyed at a group of whites arriving in a bus to gawk at a place they considered a sacred battlefield? Would someone yell at us? Would we even be safe in this bad neighborhood?

We got off the bus and gathered in the grass nearby. Stephanie introduced a man named DeMarco Davidson to us. He's a pastor and also works with the Michael Brown Foundation.

He introduced himself and asked us a question: "What comes to mind when you think of Ferguson?" Our answers varied from not even knowing it existed until Brown's shooting to fears of being in the area because it's so violent. DeMarco then spoke to us about what life was like before, during, and after the shooting. He told us about the racial tension that already existed between the police force and residents, noting his regret that the words "police" and "force" are even used together in our country. He said people often accuse him of having an agenda, which he acknowledges by saying, "I do have an agenda!" His agenda is helping people hear the story of Mike Brown and what happened in Ferguson, and working for healing and against the "othering" we do when we draw lines between people.

DeMarco then told us what happened on August 9, 2014. He said he could tell the story of Mike Brown and his life, or he could tell the story of the Brown family's experiences, or the story of their church, or the people who live in this area. "But I'll tell the story using the words of Officer Darren Wilson, who murdered Mike Brown. And I use the word 'murdered' on purpose." DeMarco quoted court documents and testimony given by Darren Wilson to tell the story of what happened, especially that day in the hours after the shooting. He told us that Brown's body laid in the street for four and a half hours, the amount of time it would take for you to drive to Kansas City or Memphis. He was angry that Brown's body wasn't covered up and it lay exposed. As he talked, he would point down the road to a patch of new asphalt that had been poured. He reminded us the shooting happened in the heat of August and Brown's body and blood were left exposed for hours, baking into the pavement. After the body was removed, the blood couldn't be so the city tore up the pavement and poured new asphalt.

DeMarco invited us to walk down the street to the spot, and to see a small memorial that was placed there. We walked quietly, observing the cars driving by and the people going about their lives in the apartments.

We stopped on the sidewalk adjacent to the new pavement patch, then crossed the road to stand on the opposite sidewalk where a dove has been placed to mark the location parallel to where Brown's body lay.

A resident in the building directly behind us came out on her balcony and DeMarco waved to her. She told us she was there the day Michael Brown died. DeMarco spoke to our group to say he doesn't know who she is, but he tries to be friendly to all the neighbors when he comes out to Canfield Drive. He wants them to know he's not there to cause problems, and he also told us that he speaks to Michael Brown's parents before he visits the area. He wants the Browns to know what he's doing there each time.

We walked back toward our bus, then past it to visit a plaque that was placed in another sidewalk as a memorial to Michael Brown.

It was time for us to load the bus and head to our next stop. I sat with Mary again on the bus and we chatted about what we had just learned. She asked about my experience growing up in the South, and I told her about living in an affluent, predominantly white county. I explained there was a white boy in middle school that a bunch of classmates picked on when they found out he was a member of the KKK, and the kid eventually left our school because of it. I think we patted ourselves on the back for that, as if it proved we weren't racists and there could be progressive whites in our white-dominated school. I also told her about high school, when some of my friends and I made it a point to invite fellow black students into our lives.

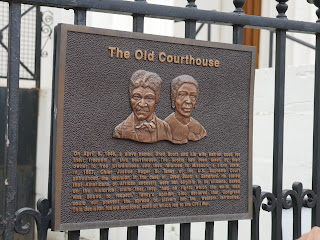

Our second Sankofa stop was at the Old St. Louis County Courthouse, where the Dred Scott trial was held.

We had a limited time to walk through the building and read a few of the displays about Dred Scott. I wandered, knowing I'd have to come back to read the exhibits in-depth.

Jessica, another woman on the Sankofa, and I happened upon a park ranger who was giving a tour to a group and allowed us to tag along for the last 10 minutes of his speech. He unlocked a gate to an upstairs courtroom so we were permitted to enter and actually sit in the courtroom chairs.

He explained this was likely the courtroom where the Dred Scott trial was held. He told us the background of the case, and how it dragged on for 11 years. A large portion of Scott's legal fees were covered by the Blow family, his original owners. Eventually, Scott's legal owner (Widow Emerson, who had remarried a man who happened to be an abolitionist), sold the Scotts back to the Blow family for $1 each (a total of $4), and the Blows gave the Scotts their freedom.

The fact that the Blow family (former slave owners) changed their original beliefs and were so committed to abolishing slavery that they paid for some of Scott's legal fees started to unravel me. I wanted to sit in that courtroom and consider this, but Jessica and I knew we needed to get back to our group. They were all meeting outside the courthouse. While we met, we looked toward the Gateway Arch and the Mississippi River, where ships would deliver slaves for sale on the courthouse steps.

We listened to Terry, one of the Sankofa leaders, as he read a slave's account of being sold at auction. When Terry came to the part where the slave's wife was sold to another owner, effectively separating them for life, he broke down crying because his own wife, LeShae, was just a few steps away. The tears started flowing for many of us, thinking what it would be like to lose your beloved like that. What a horrific experience, and knowing it was normal for slaves makes me feel such shame and grief.

After reading the slave's story, Terry passed around some historical photos of lynchings and whites attacking blacks. The grainy photos were difficult to look at, not because of the print quality but because of what they captured. What really turned my stomach was the look on the faces of many whites in the photos. There were smiles and glee, even hints of laughter on the faces - including the children in the photos.

Terry remarked that through the decades, we have been taught to listen to the narrative of the blacks as they explained their lives of slavery. He said that was appropriate, of course, but somewhere along the way we stopped listening to the white narrative. He pointed to a smiling white girl in one photo and asked, "What did this do to her? What is her story?" He has heard many people discuss slavery saying it was something done in previous generations, and it's something that we don't have to own because we didn't DO it ourselves. But for Christians, we understand the ramifications of sin that our original ancestors (Adam and Eve) chose on our behalf, and we live under the ramifications of that sin - maybe not willingly, but we know there's not much we can do to change sin's impact on us. Terry asked why we don't have that same sense of ownership in regards to prior ancestors' involvement with beliefs that certain races are superior to others.

That unraveling I mentioned a few paragraphs above? It was in full swing now. I had never considered a slave auction in regards to my personal story, nor had I felt compelled to take responsibility for my ancestors' poor decisions. The "ick" feeling grew darker and heavier in my heart.

We left the Courthouse and drove to our third stop, the Mary Meachum Freedom Crossing. It was part of the Underground Railroad.

As we pulled into this stop, I looked at the Mississippi River and the shore of Illinois on the other side and imagined someone saying to me, "Your freedom is on the other bank of this river. If you want it, you have to swim to it." I watched the river's strong current and thought I could possibly drown if I tried to swim across. If I were trying to get to the free state of Illinois on the other side, would I attempt the swim? Or would I choose safety (and slavery) on this side of the river?

Our group gathered in a metal building used as a rest stop for people on the Mississippi Greenway and we spoke about the Underground Railroad. One of our leaders, Rev. Mike Atty, read a poem about a river, then we were allowed to look at the river from the building's balcony or walk down the trail to see the crossing. Rain had started drizzling, but I decided to follow the trail anyway with a few others. We came to a set of broken stairs that lead down the riverbank. I snapped a few photos, then headed back to the bus.

As the bus pulled away I was distracted by a phone call from my husband to discuss some details about our kids and schedules, so I missed the group discussion on the bus. Shortly after, we arrived at our fourth stop: First Baptist Church of St. Louis.

This fourth stop has ties to our third stop. It's part of the church Mary Meachum and her husband, John Berry Meachum, helped start in 1825: First African Baptist Church. This was the first Protestant church for African Americans in St. Louis. The Meachums also ran a school through the church, disguised as a Sunday school class because slaves and blacks weren't allowed to be educated at the time.

We were welcomed into the church's sanctuary by the pastor's wife, who received a gift book from our Sankofa leaders. The pastor, Rev. Henry Midgett, then told us about the church's history.

We heard one of the first pastors died while preaching in the pulpit, and it happened again to another pastor 100 years after the first. Rev. Midgett told us the first building burned in 1940 and was rebuilt. He explained the fountain behind the choir loft, which is also the church's baptismal font. On the first day of church after the building was rebuilt, the pastor asked everyone to pick up a rock on the way to service. The rocks were collected and later used in the mural. Water trickles down, cascading over the cross and into the glass basin at the bottom.

Everyone walked to the basement for lunch: sub sandwiches, chips, and packs of the sweetest pineapple many of us ever tasted. We were encouraged to sit by someone new, so I placed my lunch box on a random table. I ended up sitting beside Niah (Tasha's aunt), April, and Terry. We chatted while we ate, then a church elder who sings with the St. Louis Symphony agreed to sing for us. He got some help from two ladies to sing a portion of "Lift Every Voice and Sing."

The elder explained to us that people commonly call that song the Black National Anthem. He said that's incorrect; his national anthem is "The Star Spangled Banner." This song can be called the Black Anthem, but not the national anthem.

While we ate, Terry overheard talk at the table behind him. Cindy, a white woman, had asked Matthew, a black man, what he wants someone of a different race (specifically, the white race) to know. Terry asked Cindy to repeat the question for everyone to hear, then a few of the black people in the room gave their answers.

The church elder who sang explained how he'd never experienced racism until he went into the military. He grew up in a predominantly black area in St. Louis, so he was never confronted with it until he served our country. He also expressed his desire for the younger generation to learn better values, and for their parents to teach those values to them instead of letting bad behavior. The pastor's wife, Jackie, shared an experience of shopping with her daughter. One of the white salesladies threw away her daughter's own clothes when her daughter left the changing room to show Jackie her outfit. It was a heartbreaking story, and a shock for a lot of the whites in the room to hear. But many of the blacks in the room concurred with Jackie, saying they've had similar experiences of racism.

Matthew gave his answer to the question: he wants our white culture to realize how much of the United States was built by the twelve generations of black slaves, an entire population of unpaid labor that contributed to the current success of our country. Matthew, his daughter Niah, and his granddaughter Tasha are part of the Unpaid Labor movement, which calls for remembering our country's history in order to heal race relations. Tasha told me later that we can't ignore our past and we must embrace it for healing to happen, for mistakes to be acknowledged, and for those who sacrificed to be properly honored. As their website says, "without black, there would be no red, white, and blue."

It was time for us to move on to our fifth stop, Fairgrounds Park Pool and nearby Beaumont High School.

The pool at Fairgrounds Park was the site of a riot in 1949, started by whites when blacks were allowed to use the pool for the first time. City officials had opened the pool to blacks after a federal court case ruled a law prohibiting blacks from public golf courses was a violation of the 14th Amendment. Whites gathered at the pool, shouting and harassing the black children who were swimming. It led to a riot that made national headlines.

Across the street from the park is Beaumont High School. I've been inside Beaumont before, when I was involved in a mentoring program about 15 years ago. It is important to our Sankofa journey because it was one of the first all-white schools in St. Louis to desegregate in 1954. But in the 1970s, it was re-segregated and became an all-black high school. It is currently closed. The rain kept us from getting out of the bus at the park and the high school, so I'd like to go back and visit the park especially some other time.

Our next stop was on the edge of Pruitt-Igoe, a high-rise public housing development that was built in 1954. It was a massive failure, and the buildings were demolished in the '70s.

Since I grew up in Georgia, I wasn't aware of Pruitt-Igoe's existence, failure, or the fact that it was such a sore spot in St. Louis history. Before the Sankofa, I watched a documentary called The Pruitt-Igoe Myth and it helped me understand more of the history. There isn't much to see now because the area is under development again, after years of abandonment.

Our seventh stop was Jefferson Bank, the site of protests and demonstrations in 1963.

The bank and the demonstrations held around and inside it represent the most significant parts of the St. Louis civil rights movement in the '60s. The building is still there, but the bank has moved and expanded to other areas in St. Louis.

The deposit window is still embedded in the outside wall.

Our next Sankofa stop wasn't really a stop; it was more of a drive. We left Jefferson Bank and drove to Delmar Boulevard. Rev. Atty, a pastor with Metropolitan Congregations United, asked us to pay attention on the drive and see what we might notice. He said racism isn't just about an attitude, it also concerns "where we allow some and not others."

We drove down what is called the Delmar Divide, because this street divides racial lines in an obvious way: traditionally, homes to the north of Delmar are undervalued and homes to the south are much more pricey. Besides property values, there's a marked difference in incomes, racial makeup, and education. Before watching the Pruitt-Igoe Myth and taking this Sankofa journey, I had never heard of racially restrictive covenants or a practice called redlining. (I can't tell you how uneducated and embarrassed I feel to admit that!) I was shocked to learn there were - and still are! - realtors who diverted home buyers from certain areas because of their race.

We stopped at the end of Delmar Boulevard and discussed what we saw. Some people mentioned the state of property upkeep or disrepair, others said they noticed a change in types of businesses on different sides of the street (Aldi versus Straub's grocery store). Rev. Atty quoted the bible's directive to love your neighbor, but the question is who is your neighbor? He pointed out the fact that in our city, the Missouri River is the Delmar Divide for our counties. What do we do with these divides? Do we let them continue to exist and divide, or do we try to cross them and find common ground? Rev. Atty said we must focus not on creating a "safe space" for people to gather and grow, but a brave space. We're not here to stay safe and unchallenged; we're here to be brave and to grow by sharing and learning.

Our eighth stop was at the Shelley House, which is a National Historic Landmark.

This property was the focus of the Supreme Court case Shelley v. Kraemer, which made racially restrictive covenants unenforceable in court. You can see the stone that designates this an historic landmark in the front yard of the house, but you can't see the brass plaque that describes what the house is. Why? Vandals recently stole the plaque. (And this was not the first stop on our Sankofa that had vandalism; the Freedom Crossing was also vandalized and the historic marker was damaged.) As we drove off, Terry told us he works in the mortgage business and still regularly comes across racially restrictive covenants in paperwork he handles. They aren't legal covenants, but they're still embedded in our culture.

Our ninth stop was one of the most moving and sacred ones for me. Our road trip ended in Calvary Cemetery, at the grave of Dred Scott.

Scott died only sixteen months after he was given freedom by Taylor Blow. I read that Scott was originally buried in another cemetery, but Taylor Blow moved the grave to Calvary when the other cemetery was closed. Calvary is a Catholic cemetery, but allowed burial of non-Catholic slaves if they had Catholic owners. I assume even though Dred Scott was a free man, Taylor Blow was somehow able to get his burial approved.

There's a tradition of people leaving coins on Dred Scott's grave, especially Lincoln pennies as a tribute to President Lincoln's participation in freeing the slaves. We gathered around the grave, speaking a few words.

We prayed together before boarding the bus one last time.

Before boarding the bus, I placed my penny and a rock on Dred Scott's grave. I picked up the rock at the start of our Sankofa, when I was on Canfield Drive learning about Michael Brown's death. I planned to take it home with me, but decided it belonged at the cemetery. It felt like closing the circle from the past to the present.

We arrived back where we started, at New Voice Church. I felt weighed down with a lot more emotional baggage like shame and remorse, mixed with a glimmer of liberation and hope.

After a bathroom break and helping ourselves to pizza and salad, we settled in to our tables to talk a bit. I sat at a table with my friend Gina, her sister Jenny, and a woman named Shantel who Gina and Jenny spoke with throughout the day. Shantel told me some of the stories she had shared with Gina and Jenny earlier. One of them was a story about trying to bless a woman in a white, upscale grocery checkout line only to be told "We don't accept food stamps here." Shantel wasn't on food stamps, nor was she planning to use them. The white cashier assumed the black shopper only had food stamps for her purchase.

Shantel also told us about a recent party she hosted, called a Conversation Party. She described inviting people from different walks of life to come with two questions that would be asked anonymously and answered by the gathered people. I was fascinated by this, and inspired by her curiosity of the world and the people in it. I told her she reminds me of Bob Goff, which anyone who knows me KNOWS that is a big compliment! Shantel didn't know who Bob Goff was, and my friend Gina looked at me and knew I was about to go all Bob Goff myself. I told Shantel about Bob's book Love Does, and asked for her address so I could mail a copy to her.

Our group moved from the eating portion of dinner into the experience processing portion. Rev. Atty spoke, saying racial reconciliation isn't only about how some people are born already on second base, while others haven't even gotten up to bat. It's educating ourselves about the past then learning how to rectify it and avoid it, then talking to others about it. But first you must learn through events like these, because you can't teach something you don't know.

I thought to myself, "It isn't about changing THE world, but about changing MY world." If we can all do that, THE world will change.

Rev. Atty commented that we often talk about oppression and how it wrongs the oppressed, but we don't discuss how it wrongs the oppressor. He said slavery caused whites to lose their ethnicity. They became simply "white" instead of British-American or Polish-American or German-American, and so on.

Then Rev. Atty said, "Using only one word, describe today's experience or what you feel after experiencing today's Sankofa." Our answers ranged all over the place. Words like hopeful and encouraged butted up against words like sorrow and burdened. I had a list of words I could have spoken such as guilt, remorse, curious, ashamed, embarrassed, and grieved, but ignorant was at the top of the list for me.

I consider myself a mostly intelligent person, aware of the real world and attuned to a general sense of knowledge about the goings on around me. The Sankofa journey blew that assumption out of the water, exposing my ignorance and lack of education. I felt disgusted by my ignorance. There's so much racially divisive history in St. Louis that I was unaware of! How could I have been so blind? But I did give myself a slight bit of grace when I realized this truth: I can assume there's the same kind of history of racial unrest in every American city (some more than others, of course), but most white Americans have never taken the time to dig and find it. Maybe that's because of a lack of interest, or maybe because we simply never needed to dig. Why would we? It's awkward and hard and embarrassing and heavy.

Someone mentioned the tension they felt during the day's journey, and Rev. Atty commented that sometimes the tension is necessary and can even be good, moving us into health. He compared it to a piano: "If there's no tension, a piano key can't make music."

Rev. Atty next asked us, "What was THE moment for you today?" Was there an Aha! moment, or a specific point in the day when something made sense in a way it never had before? I raised my hand, then proceeded to babble a bunch of randomness that didn't sound in my head like what came out of my mouth.

I started by describing the moment at the Courthouse when I realized the Blow family went from participating in slavery to abolishing it and supporting Dred Scott's legal case. A slave owner's heart was transformed drastically enough for him to, first, forgive his own actions so he could become a abolitionist and, then, to pursue his former slave's freedom. And here's me, in 2018, at the end of a day when my ignorance has been exposed, my heart has been mired in guilt, and I feel ineffective and insufficient. How can I possibly expect to move forward and help right those wrongs?

Then I described the related moment I had on the Courthouse steps, when Terry was reading the account of the slave couple being separated by sale and how that affected me. Terry had asked us about the white narrative in all those photos, which I hadn't really considered. I told everyone that I've looked at racism as a past problem, thinking "if I'm nice" to black people now, the problem has been solved. I have always assumed I had slave-holding relatives who lived about five generations before me, which means it didn't involve me. But earlier in the day, Tasha and I were talking on the bus and I told her about my grandmother's black maid named Pinkie, who raised my dad and his siblings. From what I understand, it was like the book/movie The Help. And that was only one generation before me! So the day's journey brought realization that racism wasn't that long ago for me and my family. The Sankofa also helped me see the ways I've tolerated racism and sometimes even contributed to it, even if I wasn't fully aware of it. That grieves me.

Tasha raised her hand to answer Rev. Atty's question too. She spoke about some of the moments she experienced and explained some of her family history. She has aunts and female relatives who were the black maids like my family's Pinkie, and Tasha said she had never considered the story from the side of the families they served until she and I talked earlier. While I felt shame, Tasha said it helped her feel hopeful and gave her understanding. I was blown away by that and wanted to respond, but Rev. Atty wanted to hear from people who hadn't spoken yet.

One man talked about what he learned and how it was good to speak these things out loud with whites, especially when a white woman inquired about his experiences with racism. Rev. Atty asked the man, "How many times have you had a white woman ask how you feel?" The man chuckled out a response: "It doesn't happen."

LaShae described what black life is like in a white culture. She often puts on a mask to navigate the world outside her front door, learning the pop culture interests of whites, like music and TV shows, all while trying to squelch her ethnicity. She said as a black, you don't want to stand out and isolate yourself from the white world. Tasha and Niah agreed, saying they have coworkers who don't know anything about them because they're never asked but they know plenty about the whites in their lives because it would be rude or stir up tension if they didn't try to fit into the white world.

Terry spoke up, saying, "We have to coexist without you insisting I be you!"

Rev. Atty said it's important for us to not just walk in someone else's shoes, but to embody the other person's experience. And even though our current racial tensions might not be from anything we specifically did, it still needs to be dealt with and not ignored.

Cindy, one of the white participants, said one of the things she learned during the day was "the whiter you are, the safer you are."

Then Rev. Atty's asked his last question: "What's your next step?" The answers ranged from things like researching, reading, seeking people from different backgrounds, and having a lot more compassion for people of color in their lives. One white woman said it helped her understand what her black boyfriend has endured that she never understood before.

The first word that came to my mind was grieve. I felt like getting in the car and weeping the whole way home for the losses and damage that people have done (and are still doing). I knew I would need to verbally process the Sankofa, and yet I wanted to stop speaking words that jumble my head even more. I said I wanted to not speak for a few days and my friend Greg muttered, "That would be a miracle." Ha!

After our dinner and discussion ended, I exchanged contact information with Rev. Atty and Shantel. I discussed plans to have Rev. Atty come barbecue with my husband some day, and made a promise to order Bob Goff's book for Shantel and deliver it to her soon.

Gina remembered I hadn't responded to Tasha's words earlier, so she snagged Tasha before she left. I told her I was shocked so many of the blacks in the room chose their "one word" to be something positive like hopeful or encouraged. Tasha had used a positive word too, and I told her that confused me. How could she be encouraged after learning all we learned today? It didn't encourage me, it shamed and horrified me! But Tasha disagreed, explaining it was encouraging for her because - finally! - whites and blacks spent the day openly talking about our shared history, along with change and reconciliation. That encourages her because it means we can continue to learn and share each other's viewpoints. She said, "I thought you knew how we felt." Those words clarified the day for me, and suddenly I had tears in my eyes.

Tasha thought I, as a white woman, knew how she felt. And in spite of that knowledge, I existed with a "live and let live" kind of mentality, never trying to repair past hurts or even reach across the dividing lines to seek out someone of another color. I put myself in this scenario: imagine I felt small and invisible, forced to play along in a game where the rules are against me. How frustrating that would be to feel like a second class citizen, ignored and irrelevant, and then to have no one acknowledge my feelings. After a while, I think I'd get pretty mad! Especially at the people who seem to see me but obviously don't care enough to interact with me or rectify our disparities... never knowing that those people I'm angry with really don't know what my life is like.

To me, it sounded like Tasha didn't realize that whites don't know what her life as a black woman is like. Both races assume the other knows all this history and all these feelings, and chooses not to do anything about it. And until we talk openly about these issues, we'll go on assuming and driving the wedges deeper between us.

The Sankofa encouraged Tasha to have hope that we'll keep learning and talking and those wedges between us will diminish. And when you put it that way, I can see hope too!

Gina, Jenny and I left the church at 6pm and drove back to Jenny's house and my car. We shared our reactions to the day and discussed what we might do next. I knew more than anything, I needed to get a good night's rest and let my brain have time to make sense of things.

-----

Before April 14's Sankofa, I thought we as a country could simply agree to move beyond our country's past racial history and all the tension would go away. I wanted to erase slavery and the impact it's had on our country and our people. But the Sankofa taught me slavery can't be erased. It was abolished, but I can't expect that to mean it was erased. There's too much that needs to be acknowledged, not forgotten. So instead of moving forward by forgetting the past, the Sankofa helped me understand the only way to move forward is by honoring the past. It seems contradictory, right? Delving into our past seems like it would stir up pain and fan the flames of racial tension, not ease it. But I'm finding that isn't true, especially in God's kingdom. Sometimes what makes the least sense is what's best for our growth.

I have been writing this blog post off and on for almost three weeks, as my brain is still making sense of the experience. I've had a few more Aha! moments as I assess my lifelong prejudices, my actions (or inactions), and the duty I now feel to change my little corner of the world. I still don't know what that looks like, but I do know this blog post is a good start for me to express and share what I'm feeling.

Two weekends ago, I had an experience that changed my thinking on racial reconciliation in our country, in general, and in St. Louis, specifically.

It's called a Sankofa, a word I had never heard before January of this year. I didn't fully understand it until I experienced it, and I'll try to give you the best insight I can. But there comes a point when words can't express what an experience involves, so I highly recommend you tackle something like this yourself.

In January my friend Gina invited me and our other best friend, Kristen, to attend an event called a Sankofa, hosted by her sister Jenny's church. Gina described it like this:

"A day spent visiting/exploring/hearing stories about St. Louis landmarks that are relevant to the story of our black brothers and sisters. Like they visit where the Michael Brown shooting occurred, the Dred Scott trial was held, and many places we may have been but not known about the historical relevance. You are paired with an individual of African American descent for the day (or grouped if there are not enough individuals) to unpack the sights and experiences."

What exactly is a Sankofa? Here's one explanation I found online: "Sankofa is a sacred ancestral term from the Akan people of Ghana, West Africa and can be translated as 'We must go back and reclaim our past so we can move forward - so we understand WHY and HOW we came to be who we are today!'"

What exactly is a Sankofa? Here's one explanation I found online: "Sankofa is a sacred ancestral term from the Akan people of Ghana, West Africa and can be translated as 'We must go back and reclaim our past so we can move forward - so we understand WHY and HOW we came to be who we are today!'"The Sankofa symbol is a mythical bird with feet facing forward while the head rotates backward. This image illustrates the idea of forward direction while acknowledging where you've been.

I didn't fully grasp what these explanations and concepts mean, but accepted Gina's invitation to join her and Jenny.

Why would I say yes to something I didn't quite understand? Something that sounds likely to be awkward and intense? And something that sounds, to a person like me (who has been known to insert my foot in my mouth on numerous occasions), like a situation where I'm likely to say words or act in a way that is very ignorant and will result in more foot-mouth experiences?

I said yes because Gina, Kristen, and I have been talking about bridge building for a few years. There's a quote by JF Newton that says, "We build too many walls and not enough bridges." My friends and I have taken that to heart, talking about how to intentionally seek people who are different than us so we can cross the barriers and dividing lines that seem to separate us. We've been challenging and encouraging each other to do this with people of different gender identities, faith backgrounds, sexual preferences, and skin colors.

The Sankofa seemed to align with those intentions, so I said yes! (Unfortunately, Kristen couldn't make it - but I'm pretty sure she'll be on the next one!)

I wasn't quite sure what to expect, but I showed up with an open heart and a praying soul. God walked with me throughout the day (and into the next 24 hours, too - a story for another post), and I'm so excited and humbled to share my experience with you here.

Before I get to the exhaustive details of the highlights and stops we made, let me give you the bird's-eye-view of what I carried with me when it was over.

My first emotion was humility, due to my ignorance. I admit I was uneducated (and still am!) about a number of system-wide policies that were placed on blacks in our country. I knew segregation existed in the past, but I considered it ancient history. And if not quite ancient, at least it was long enough before I was born that it feels ancient. Thanks to the Sankofa, I realized these things aren't ancient, nor are they exactly history. They're current events. And the fact that I was so ignorant of these things makes me cringe, because I'm embarrassed to admit my vantage point never covered other people's views.

My amateur education in race relations started with some videos I watched before the Sankofa and a few articles I read, like these:

Since I didn't grow up in St. Louis, I was unaware of the history of race relations in my city. The outbursts and emotions that surfaced after Michael Brown's shooting in Ferguson caught me by surprise, but I've heard from other native St. Louisans that it wasn't a huge surprise for them. Watching those videos I linked (above) and reading that article educated and awakened me to new views.

But it wasn't until I experienced the Sankofa that my education transformed from information into narration. The information went from my head to my heart.

We started the morning meeting at a church in St. Ann. We made introductions and got an overview of the day, and Stephanie (our leader) asked us to be brave and mingle with other people we don't know. She even went so far as to ask the white participants to make an effort to sit by a black participant on the bus so we could share our stories. After praying, we boarded a school bus and our trip began.

I sat with my friend Mary, who I already knew because we used to work together at our church. We also went to Guatemala together last October, so it was like a bus reunion of sorts for us. Mary started chatting with others across the aisle, and the black woman in the seat in front of me turned around to introduce herself. Her name was Tasha, and she asked me if this was my first Sankofa.

Poor Tasha, she asked me one question and my awkwardness took over. I was so afraid of saying something stupid or offensive that I just started a verbal vomit of the story of my friend inviting me and Kristen on the trip. I told her how the Bridge Building mindset started for me, when my gay friends asked me to speak at their wedding. That gave us common ground, as she asked me about how I've talked with my kids about homosexuality. She said she's been wondering how to start the conversation with her five- and six-year-olds, and I was happy to share my experience. (Poor Tasha, listening to me ramble!)

We arrived at our first stop of the day: Canfield Drive in Ferguson, where Michael Brown was shot by a police officer in 2014.

Before the Sankofa started, I knew we'd be going to this place and it was the stop I was most nervous about. Like the rest of the country, I had seen television footage of the scene at Canfield Green Apartments plus hours of video of protests and riots in Ferguson. I had assumed Ferguson was a dangerous place, and Canfield Green Apartments would NOT be a good place for a white person to be. I don't know what I imagined would happen: would black residents be annoyed at a group of whites arriving in a bus to gawk at a place they considered a sacred battlefield? Would someone yell at us? Would we even be safe in this bad neighborhood?

We got off the bus and gathered in the grass nearby. Stephanie introduced a man named DeMarco Davidson to us. He's a pastor and also works with the Michael Brown Foundation.

He introduced himself and asked us a question: "What comes to mind when you think of Ferguson?" Our answers varied from not even knowing it existed until Brown's shooting to fears of being in the area because it's so violent. DeMarco then spoke to us about what life was like before, during, and after the shooting. He told us about the racial tension that already existed between the police force and residents, noting his regret that the words "police" and "force" are even used together in our country. He said people often accuse him of having an agenda, which he acknowledges by saying, "I do have an agenda!" His agenda is helping people hear the story of Mike Brown and what happened in Ferguson, and working for healing and against the "othering" we do when we draw lines between people.

DeMarco then told us what happened on August 9, 2014. He said he could tell the story of Mike Brown and his life, or he could tell the story of the Brown family's experiences, or the story of their church, or the people who live in this area. "But I'll tell the story using the words of Officer Darren Wilson, who murdered Mike Brown. And I use the word 'murdered' on purpose." DeMarco quoted court documents and testimony given by Darren Wilson to tell the story of what happened, especially that day in the hours after the shooting. He told us that Brown's body laid in the street for four and a half hours, the amount of time it would take for you to drive to Kansas City or Memphis. He was angry that Brown's body wasn't covered up and it lay exposed. As he talked, he would point down the road to a patch of new asphalt that had been poured. He reminded us the shooting happened in the heat of August and Brown's body and blood were left exposed for hours, baking into the pavement. After the body was removed, the blood couldn't be so the city tore up the pavement and poured new asphalt.

DeMarco invited us to walk down the street to the spot, and to see a small memorial that was placed there. We walked quietly, observing the cars driving by and the people going about their lives in the apartments.

We stopped on the sidewalk adjacent to the new pavement patch, then crossed the road to stand on the opposite sidewalk where a dove has been placed to mark the location parallel to where Brown's body lay.

A resident in the building directly behind us came out on her balcony and DeMarco waved to her. She told us she was there the day Michael Brown died. DeMarco spoke to our group to say he doesn't know who she is, but he tries to be friendly to all the neighbors when he comes out to Canfield Drive. He wants them to know he's not there to cause problems, and he also told us that he speaks to Michael Brown's parents before he visits the area. He wants the Browns to know what he's doing there each time.

We walked back toward our bus, then past it to visit a plaque that was placed in another sidewalk as a memorial to Michael Brown.

It was time for us to load the bus and head to our next stop. I sat with Mary again on the bus and we chatted about what we had just learned. She asked about my experience growing up in the South, and I told her about living in an affluent, predominantly white county. I explained there was a white boy in middle school that a bunch of classmates picked on when they found out he was a member of the KKK, and the kid eventually left our school because of it. I think we patted ourselves on the back for that, as if it proved we weren't racists and there could be progressive whites in our white-dominated school. I also told her about high school, when some of my friends and I made it a point to invite fellow black students into our lives.

Our second Sankofa stop was at the Old St. Louis County Courthouse, where the Dred Scott trial was held.

We had a limited time to walk through the building and read a few of the displays about Dred Scott. I wandered, knowing I'd have to come back to read the exhibits in-depth.

Jessica, another woman on the Sankofa, and I happened upon a park ranger who was giving a tour to a group and allowed us to tag along for the last 10 minutes of his speech. He unlocked a gate to an upstairs courtroom so we were permitted to enter and actually sit in the courtroom chairs.

He explained this was likely the courtroom where the Dred Scott trial was held. He told us the background of the case, and how it dragged on for 11 years. A large portion of Scott's legal fees were covered by the Blow family, his original owners. Eventually, Scott's legal owner (Widow Emerson, who had remarried a man who happened to be an abolitionist), sold the Scotts back to the Blow family for $1 each (a total of $4), and the Blows gave the Scotts their freedom.

The fact that the Blow family (former slave owners) changed their original beliefs and were so committed to abolishing slavery that they paid for some of Scott's legal fees started to unravel me. I wanted to sit in that courtroom and consider this, but Jessica and I knew we needed to get back to our group. They were all meeting outside the courthouse. While we met, we looked toward the Gateway Arch and the Mississippi River, where ships would deliver slaves for sale on the courthouse steps.

We listened to Terry, one of the Sankofa leaders, as he read a slave's account of being sold at auction. When Terry came to the part where the slave's wife was sold to another owner, effectively separating them for life, he broke down crying because his own wife, LeShae, was just a few steps away. The tears started flowing for many of us, thinking what it would be like to lose your beloved like that. What a horrific experience, and knowing it was normal for slaves makes me feel such shame and grief.

After reading the slave's story, Terry passed around some historical photos of lynchings and whites attacking blacks. The grainy photos were difficult to look at, not because of the print quality but because of what they captured. What really turned my stomach was the look on the faces of many whites in the photos. There were smiles and glee, even hints of laughter on the faces - including the children in the photos.

Terry remarked that through the decades, we have been taught to listen to the narrative of the blacks as they explained their lives of slavery. He said that was appropriate, of course, but somewhere along the way we stopped listening to the white narrative. He pointed to a smiling white girl in one photo and asked, "What did this do to her? What is her story?" He has heard many people discuss slavery saying it was something done in previous generations, and it's something that we don't have to own because we didn't DO it ourselves. But for Christians, we understand the ramifications of sin that our original ancestors (Adam and Eve) chose on our behalf, and we live under the ramifications of that sin - maybe not willingly, but we know there's not much we can do to change sin's impact on us. Terry asked why we don't have that same sense of ownership in regards to prior ancestors' involvement with beliefs that certain races are superior to others.

That unraveling I mentioned a few paragraphs above? It was in full swing now. I had never considered a slave auction in regards to my personal story, nor had I felt compelled to take responsibility for my ancestors' poor decisions. The "ick" feeling grew darker and heavier in my heart.

We left the Courthouse and drove to our third stop, the Mary Meachum Freedom Crossing. It was part of the Underground Railroad.

As we pulled into this stop, I looked at the Mississippi River and the shore of Illinois on the other side and imagined someone saying to me, "Your freedom is on the other bank of this river. If you want it, you have to swim to it." I watched the river's strong current and thought I could possibly drown if I tried to swim across. If I were trying to get to the free state of Illinois on the other side, would I attempt the swim? Or would I choose safety (and slavery) on this side of the river?

Our group gathered in a metal building used as a rest stop for people on the Mississippi Greenway and we spoke about the Underground Railroad. One of our leaders, Rev. Mike Atty, read a poem about a river, then we were allowed to look at the river from the building's balcony or walk down the trail to see the crossing. Rain had started drizzling, but I decided to follow the trail anyway with a few others. We came to a set of broken stairs that lead down the riverbank. I snapped a few photos, then headed back to the bus.

As the bus pulled away I was distracted by a phone call from my husband to discuss some details about our kids and schedules, so I missed the group discussion on the bus. Shortly after, we arrived at our fourth stop: First Baptist Church of St. Louis.

This fourth stop has ties to our third stop. It's part of the church Mary Meachum and her husband, John Berry Meachum, helped start in 1825: First African Baptist Church. This was the first Protestant church for African Americans in St. Louis. The Meachums also ran a school through the church, disguised as a Sunday school class because slaves and blacks weren't allowed to be educated at the time.

We were welcomed into the church's sanctuary by the pastor's wife, who received a gift book from our Sankofa leaders. The pastor, Rev. Henry Midgett, then told us about the church's history.

We heard one of the first pastors died while preaching in the pulpit, and it happened again to another pastor 100 years after the first. Rev. Midgett told us the first building burned in 1940 and was rebuilt. He explained the fountain behind the choir loft, which is also the church's baptismal font. On the first day of church after the building was rebuilt, the pastor asked everyone to pick up a rock on the way to service. The rocks were collected and later used in the mural. Water trickles down, cascading over the cross and into the glass basin at the bottom.

Everyone walked to the basement for lunch: sub sandwiches, chips, and packs of the sweetest pineapple many of us ever tasted. We were encouraged to sit by someone new, so I placed my lunch box on a random table. I ended up sitting beside Niah (Tasha's aunt), April, and Terry. We chatted while we ate, then a church elder who sings with the St. Louis Symphony agreed to sing for us. He got some help from two ladies to sing a portion of "Lift Every Voice and Sing."

The elder explained to us that people commonly call that song the Black National Anthem. He said that's incorrect; his national anthem is "The Star Spangled Banner." This song can be called the Black Anthem, but not the national anthem.

While we ate, Terry overheard talk at the table behind him. Cindy, a white woman, had asked Matthew, a black man, what he wants someone of a different race (specifically, the white race) to know. Terry asked Cindy to repeat the question for everyone to hear, then a few of the black people in the room gave their answers.

The church elder who sang explained how he'd never experienced racism until he went into the military. He grew up in a predominantly black area in St. Louis, so he was never confronted with it until he served our country. He also expressed his desire for the younger generation to learn better values, and for their parents to teach those values to them instead of letting bad behavior. The pastor's wife, Jackie, shared an experience of shopping with her daughter. One of the white salesladies threw away her daughter's own clothes when her daughter left the changing room to show Jackie her outfit. It was a heartbreaking story, and a shock for a lot of the whites in the room to hear. But many of the blacks in the room concurred with Jackie, saying they've had similar experiences of racism.

Matthew gave his answer to the question: he wants our white culture to realize how much of the United States was built by the twelve generations of black slaves, an entire population of unpaid labor that contributed to the current success of our country. Matthew, his daughter Niah, and his granddaughter Tasha are part of the Unpaid Labor movement, which calls for remembering our country's history in order to heal race relations. Tasha told me later that we can't ignore our past and we must embrace it for healing to happen, for mistakes to be acknowledged, and for those who sacrificed to be properly honored. As their website says, "without black, there would be no red, white, and blue."

It was time for us to move on to our fifth stop, Fairgrounds Park Pool and nearby Beaumont High School.

The pool at Fairgrounds Park was the site of a riot in 1949, started by whites when blacks were allowed to use the pool for the first time. City officials had opened the pool to blacks after a federal court case ruled a law prohibiting blacks from public golf courses was a violation of the 14th Amendment. Whites gathered at the pool, shouting and harassing the black children who were swimming. It led to a riot that made national headlines.

Across the street from the park is Beaumont High School. I've been inside Beaumont before, when I was involved in a mentoring program about 15 years ago. It is important to our Sankofa journey because it was one of the first all-white schools in St. Louis to desegregate in 1954. But in the 1970s, it was re-segregated and became an all-black high school. It is currently closed. The rain kept us from getting out of the bus at the park and the high school, so I'd like to go back and visit the park especially some other time.

Our next stop was on the edge of Pruitt-Igoe, a high-rise public housing development that was built in 1954. It was a massive failure, and the buildings were demolished in the '70s.

Since I grew up in Georgia, I wasn't aware of Pruitt-Igoe's existence, failure, or the fact that it was such a sore spot in St. Louis history. Before the Sankofa, I watched a documentary called The Pruitt-Igoe Myth and it helped me understand more of the history. There isn't much to see now because the area is under development again, after years of abandonment.

Our seventh stop was Jefferson Bank, the site of protests and demonstrations in 1963.

The bank and the demonstrations held around and inside it represent the most significant parts of the St. Louis civil rights movement in the '60s. The building is still there, but the bank has moved and expanded to other areas in St. Louis.

The deposit window is still embedded in the outside wall.

Our next Sankofa stop wasn't really a stop; it was more of a drive. We left Jefferson Bank and drove to Delmar Boulevard. Rev. Atty, a pastor with Metropolitan Congregations United, asked us to pay attention on the drive and see what we might notice. He said racism isn't just about an attitude, it also concerns "where we allow some and not others."

We drove down what is called the Delmar Divide, because this street divides racial lines in an obvious way: traditionally, homes to the north of Delmar are undervalued and homes to the south are much more pricey. Besides property values, there's a marked difference in incomes, racial makeup, and education. Before watching the Pruitt-Igoe Myth and taking this Sankofa journey, I had never heard of racially restrictive covenants or a practice called redlining. (I can't tell you how uneducated and embarrassed I feel to admit that!) I was shocked to learn there were - and still are! - realtors who diverted home buyers from certain areas because of their race.

We stopped at the end of Delmar Boulevard and discussed what we saw. Some people mentioned the state of property upkeep or disrepair, others said they noticed a change in types of businesses on different sides of the street (Aldi versus Straub's grocery store). Rev. Atty quoted the bible's directive to love your neighbor, but the question is who is your neighbor? He pointed out the fact that in our city, the Missouri River is the Delmar Divide for our counties. What do we do with these divides? Do we let them continue to exist and divide, or do we try to cross them and find common ground? Rev. Atty said we must focus not on creating a "safe space" for people to gather and grow, but a brave space. We're not here to stay safe and unchallenged; we're here to be brave and to grow by sharing and learning.

Our eighth stop was at the Shelley House, which is a National Historic Landmark.

This property was the focus of the Supreme Court case Shelley v. Kraemer, which made racially restrictive covenants unenforceable in court. You can see the stone that designates this an historic landmark in the front yard of the house, but you can't see the brass plaque that describes what the house is. Why? Vandals recently stole the plaque. (And this was not the first stop on our Sankofa that had vandalism; the Freedom Crossing was also vandalized and the historic marker was damaged.) As we drove off, Terry told us he works in the mortgage business and still regularly comes across racially restrictive covenants in paperwork he handles. They aren't legal covenants, but they're still embedded in our culture.

Our ninth stop was one of the most moving and sacred ones for me. Our road trip ended in Calvary Cemetery, at the grave of Dred Scott.

Scott died only sixteen months after he was given freedom by Taylor Blow. I read that Scott was originally buried in another cemetery, but Taylor Blow moved the grave to Calvary when the other cemetery was closed. Calvary is a Catholic cemetery, but allowed burial of non-Catholic slaves if they had Catholic owners. I assume even though Dred Scott was a free man, Taylor Blow was somehow able to get his burial approved.

There's a tradition of people leaving coins on Dred Scott's grave, especially Lincoln pennies as a tribute to President Lincoln's participation in freeing the slaves. We gathered around the grave, speaking a few words.

We prayed together before boarding the bus one last time.

Before boarding the bus, I placed my penny and a rock on Dred Scott's grave. I picked up the rock at the start of our Sankofa, when I was on Canfield Drive learning about Michael Brown's death. I planned to take it home with me, but decided it belonged at the cemetery. It felt like closing the circle from the past to the present.

We arrived back where we started, at New Voice Church. I felt weighed down with a lot more emotional baggage like shame and remorse, mixed with a glimmer of liberation and hope.

After a bathroom break and helping ourselves to pizza and salad, we settled in to our tables to talk a bit. I sat at a table with my friend Gina, her sister Jenny, and a woman named Shantel who Gina and Jenny spoke with throughout the day. Shantel told me some of the stories she had shared with Gina and Jenny earlier. One of them was a story about trying to bless a woman in a white, upscale grocery checkout line only to be told "We don't accept food stamps here." Shantel wasn't on food stamps, nor was she planning to use them. The white cashier assumed the black shopper only had food stamps for her purchase.

Shantel also told us about a recent party she hosted, called a Conversation Party. She described inviting people from different walks of life to come with two questions that would be asked anonymously and answered by the gathered people. I was fascinated by this, and inspired by her curiosity of the world and the people in it. I told her she reminds me of Bob Goff, which anyone who knows me KNOWS that is a big compliment! Shantel didn't know who Bob Goff was, and my friend Gina looked at me and knew I was about to go all Bob Goff myself. I told Shantel about Bob's book Love Does, and asked for her address so I could mail a copy to her.

Our group moved from the eating portion of dinner into the experience processing portion. Rev. Atty spoke, saying racial reconciliation isn't only about how some people are born already on second base, while others haven't even gotten up to bat. It's educating ourselves about the past then learning how to rectify it and avoid it, then talking to others about it. But first you must learn through events like these, because you can't teach something you don't know.

I thought to myself, "It isn't about changing THE world, but about changing MY world." If we can all do that, THE world will change.

Rev. Atty commented that we often talk about oppression and how it wrongs the oppressed, but we don't discuss how it wrongs the oppressor. He said slavery caused whites to lose their ethnicity. They became simply "white" instead of British-American or Polish-American or German-American, and so on.

Then Rev. Atty said, "Using only one word, describe today's experience or what you feel after experiencing today's Sankofa." Our answers ranged all over the place. Words like hopeful and encouraged butted up against words like sorrow and burdened. I had a list of words I could have spoken such as guilt, remorse, curious, ashamed, embarrassed, and grieved, but ignorant was at the top of the list for me.

I consider myself a mostly intelligent person, aware of the real world and attuned to a general sense of knowledge about the goings on around me. The Sankofa journey blew that assumption out of the water, exposing my ignorance and lack of education. I felt disgusted by my ignorance. There's so much racially divisive history in St. Louis that I was unaware of! How could I have been so blind? But I did give myself a slight bit of grace when I realized this truth: I can assume there's the same kind of history of racial unrest in every American city (some more than others, of course), but most white Americans have never taken the time to dig and find it. Maybe that's because of a lack of interest, or maybe because we simply never needed to dig. Why would we? It's awkward and hard and embarrassing and heavy.

Someone mentioned the tension they felt during the day's journey, and Rev. Atty commented that sometimes the tension is necessary and can even be good, moving us into health. He compared it to a piano: "If there's no tension, a piano key can't make music."

Rev. Atty next asked us, "What was THE moment for you today?" Was there an Aha! moment, or a specific point in the day when something made sense in a way it never had before? I raised my hand, then proceeded to babble a bunch of randomness that didn't sound in my head like what came out of my mouth.

I started by describing the moment at the Courthouse when I realized the Blow family went from participating in slavery to abolishing it and supporting Dred Scott's legal case. A slave owner's heart was transformed drastically enough for him to, first, forgive his own actions so he could become a abolitionist and, then, to pursue his former slave's freedom. And here's me, in 2018, at the end of a day when my ignorance has been exposed, my heart has been mired in guilt, and I feel ineffective and insufficient. How can I possibly expect to move forward and help right those wrongs?

Then I described the related moment I had on the Courthouse steps, when Terry was reading the account of the slave couple being separated by sale and how that affected me. Terry had asked us about the white narrative in all those photos, which I hadn't really considered. I told everyone that I've looked at racism as a past problem, thinking "if I'm nice" to black people now, the problem has been solved. I have always assumed I had slave-holding relatives who lived about five generations before me, which means it didn't involve me. But earlier in the day, Tasha and I were talking on the bus and I told her about my grandmother's black maid named Pinkie, who raised my dad and his siblings. From what I understand, it was like the book/movie The Help. And that was only one generation before me! So the day's journey brought realization that racism wasn't that long ago for me and my family. The Sankofa also helped me see the ways I've tolerated racism and sometimes even contributed to it, even if I wasn't fully aware of it. That grieves me.

Tasha raised her hand to answer Rev. Atty's question too. She spoke about some of the moments she experienced and explained some of her family history. She has aunts and female relatives who were the black maids like my family's Pinkie, and Tasha said she had never considered the story from the side of the families they served until she and I talked earlier. While I felt shame, Tasha said it helped her feel hopeful and gave her understanding. I was blown away by that and wanted to respond, but Rev. Atty wanted to hear from people who hadn't spoken yet.

One man talked about what he learned and how it was good to speak these things out loud with whites, especially when a white woman inquired about his experiences with racism. Rev. Atty asked the man, "How many times have you had a white woman ask how you feel?" The man chuckled out a response: "It doesn't happen."

LaShae described what black life is like in a white culture. She often puts on a mask to navigate the world outside her front door, learning the pop culture interests of whites, like music and TV shows, all while trying to squelch her ethnicity. She said as a black, you don't want to stand out and isolate yourself from the white world. Tasha and Niah agreed, saying they have coworkers who don't know anything about them because they're never asked but they know plenty about the whites in their lives because it would be rude or stir up tension if they didn't try to fit into the white world.

Terry spoke up, saying, "We have to coexist without you insisting I be you!"

Rev. Atty said it's important for us to not just walk in someone else's shoes, but to embody the other person's experience. And even though our current racial tensions might not be from anything we specifically did, it still needs to be dealt with and not ignored.

Cindy, one of the white participants, said one of the things she learned during the day was "the whiter you are, the safer you are."

Then Rev. Atty's asked his last question: "What's your next step?" The answers ranged from things like researching, reading, seeking people from different backgrounds, and having a lot more compassion for people of color in their lives. One white woman said it helped her understand what her black boyfriend has endured that she never understood before.

The first word that came to my mind was grieve. I felt like getting in the car and weeping the whole way home for the losses and damage that people have done (and are still doing). I knew I would need to verbally process the Sankofa, and yet I wanted to stop speaking words that jumble my head even more. I said I wanted to not speak for a few days and my friend Greg muttered, "That would be a miracle." Ha!

After our dinner and discussion ended, I exchanged contact information with Rev. Atty and Shantel. I discussed plans to have Rev. Atty come barbecue with my husband some day, and made a promise to order Bob Goff's book for Shantel and deliver it to her soon.

Gina remembered I hadn't responded to Tasha's words earlier, so she snagged Tasha before she left. I told her I was shocked so many of the blacks in the room chose their "one word" to be something positive like hopeful or encouraged. Tasha had used a positive word too, and I told her that confused me. How could she be encouraged after learning all we learned today? It didn't encourage me, it shamed and horrified me! But Tasha disagreed, explaining it was encouraging for her because - finally! - whites and blacks spent the day openly talking about our shared history, along with change and reconciliation. That encourages her because it means we can continue to learn and share each other's viewpoints. She said, "I thought you knew how we felt." Those words clarified the day for me, and suddenly I had tears in my eyes.

Tasha thought I, as a white woman, knew how she felt. And in spite of that knowledge, I existed with a "live and let live" kind of mentality, never trying to repair past hurts or even reach across the dividing lines to seek out someone of another color. I put myself in this scenario: imagine I felt small and invisible, forced to play along in a game where the rules are against me. How frustrating that would be to feel like a second class citizen, ignored and irrelevant, and then to have no one acknowledge my feelings. After a while, I think I'd get pretty mad! Especially at the people who seem to see me but obviously don't care enough to interact with me or rectify our disparities... never knowing that those people I'm angry with really don't know what my life is like.

To me, it sounded like Tasha didn't realize that whites don't know what her life as a black woman is like. Both races assume the other knows all this history and all these feelings, and chooses not to do anything about it. And until we talk openly about these issues, we'll go on assuming and driving the wedges deeper between us.

The Sankofa encouraged Tasha to have hope that we'll keep learning and talking and those wedges between us will diminish. And when you put it that way, I can see hope too!

Gina, Jenny and I left the church at 6pm and drove back to Jenny's house and my car. We shared our reactions to the day and discussed what we might do next. I knew more than anything, I needed to get a good night's rest and let my brain have time to make sense of things.

-----

Before April 14's Sankofa, I thought we as a country could simply agree to move beyond our country's past racial history and all the tension would go away. I wanted to erase slavery and the impact it's had on our country and our people. But the Sankofa taught me slavery can't be erased. It was abolished, but I can't expect that to mean it was erased. There's too much that needs to be acknowledged, not forgotten. So instead of moving forward by forgetting the past, the Sankofa helped me understand the only way to move forward is by honoring the past. It seems contradictory, right? Delving into our past seems like it would stir up pain and fan the flames of racial tension, not ease it. But I'm finding that isn't true, especially in God's kingdom. Sometimes what makes the least sense is what's best for our growth.

I have been writing this blog post off and on for almost three weeks, as my brain is still making sense of the experience. I've had a few more Aha! moments as I assess my lifelong prejudices, my actions (or inactions), and the duty I now feel to change my little corner of the world. I still don't know what that looks like, but I do know this blog post is a good start for me to express and share what I'm feeling.

7 comments:

Thank you for being Honest, Transparent, Real, and Open. Because of that attitude that you came in, we have formed a true GOD like friendship that will last a lifetime. Truly building bridges for Kingdom business!!!! And we will enjoy this sacred journey together like our father intended. One body, one mind, one spirit ( the Holy Spirit). I am proud to call you my friend!

Thanks a bunch,

From your new friend Shantel :)

This, my friend, is why I love you and living life with you!

Where there are bridges already built, let us humbly and lovingly travel them. Where there is none, let us patiently and carefully begin building, one step at a time!

Accurate and timely compliance is critical. The P.Tax list of Mizoram is a valuable guide for both employers and finance professionals.

my husband came back to me and start begging me to forgive him in few days' ago with the help of Dr Guba, if you are in any relationship problem i advice you to contact this great man called Dr Guba, whatsapp, +234 7077581439 or Email Gubasolutionhome@gmail.com